Private Employee’s Claim That She Was Fired for Peacefully Attending Jan. 6 Events Can Go Forward,

[ad_1]

I blogged about Snyder v. Alight Solutions, LLC (C.D. Cal.) on Jan. 27, 2021, when it was first filed, but hadn’t heard until today that on Sept. 14, 2022 there was a decision on a motion for summary judgment (by Judge Cormac Carney); the case has since settled instead of going to trial:

Plaintiff Leah Snyder alleges that Defendant Alight Solutions, LLC wrongfully terminated her employment after she posted to a private Facebook page photos of herself at the Washington, D.C. Capitol building on January 6, 2021 and positive comments about the events that took place that day. In short, the parties’ disagreement is this: Defendant argues that it lawfully terminated Plaintiff’s employment because she violated laws proscribing where demonstrations may take place on Capitol grounds. Plaintiff alleges that this reason for her termination was pretextual, and that her employment was terminated for a political motive—specifically relating to her support of former President Donald Trump—or as retaliation for reporting harassment she experienced in response to her photos and comments on Facebook….

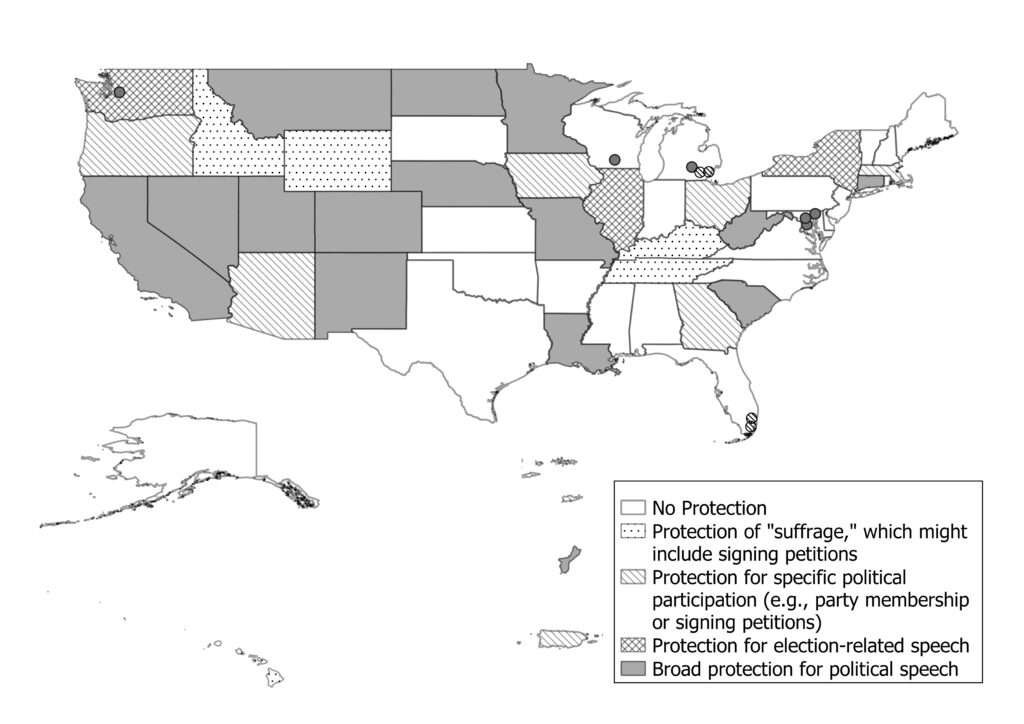

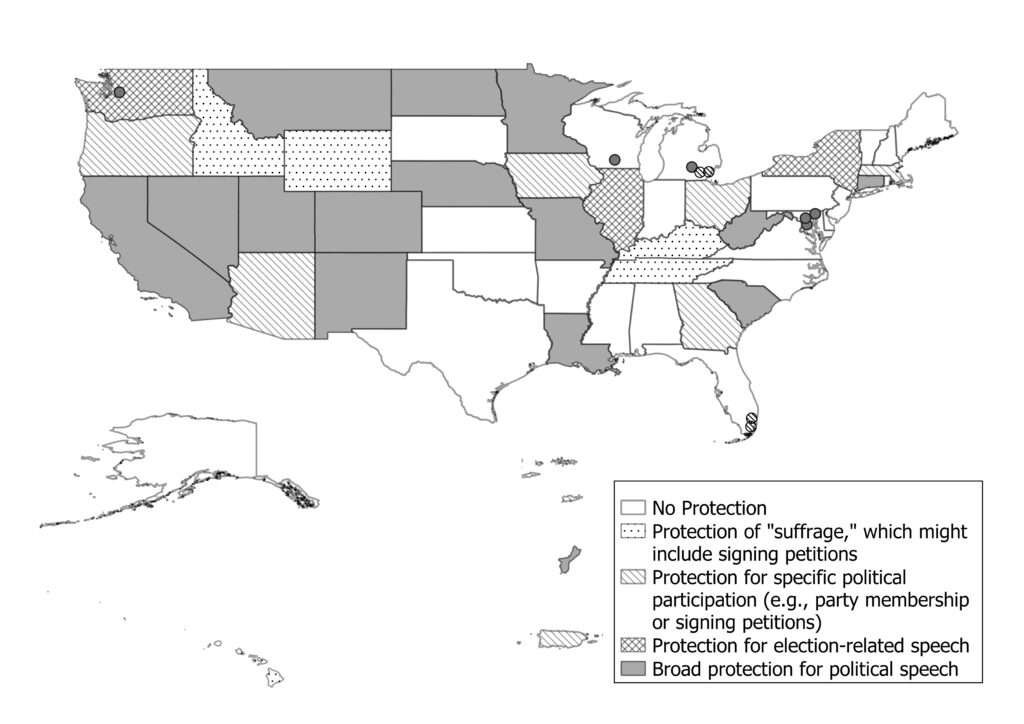

The court allowed the case to go forward to trial under California’s statutes that protect private employees’ political activity (for more on such statutes in various jurisdictions, see this article and this one):

In general, an at-will employee like Plaintiff may be terminated for an arbitrary reason, for an irrational reason, or for no reason at all. However, an employer may not terminate an at-will employee for an unlawful reason, or for a purpose that contravenes fundamental public policy. “When an employee is discharged in violation of ‘fundamental principles of public policy,’ the employee may maintain a tort action and recover damages traditionally available in such actions.” California courts recognize four categories of public policy cases: “the employee (1) refused to violate a statute; (2) performed a statutory obligation; (3) exercised a constitutional or statutory right or privilege; or (4) reported a statutory violation for the public’s benefit.”

Plaintiff alleges that she was wrongfully terminated for exercising “constitutional rights to speak freely, peaceably assemble or petition her grievances to the Government,” in violation of the public policy described in California Labor Code Sections 1101 and 1102. “Sections 1101 and 1102 … prohibit employers from interfering with ‘the fundamental right of employees in general to engage in political activity.'” “[L]iability under §§ 1101(a) and 1102 is triggered only if an employer fires an employee based on a political motive.”

{Section 1101 states: “No employer shall make, adopt, or enforce any rule, regulation, or policy … forbidding or preventing employees from engaging or participating in politics, or … controlling or directing, or tending to control or direct the political activities or affiliations of employees.” Section 1102 states: “No employer shall coerce or influence or attempt to coerce or influence his employees through or by means of threat of discharge or loss of employment to adopt or follow or refrain from adopting or following any particular course or line of political action or political activity.”}

Construing the facts in the light most favorable to Plaintiff and drawing all justifiable inferences in her favor, there is a genuine dispute of material fact regarding whether Defendant fired Plaintiff based on a political motive. Plaintiff testified that she visited the Capitol on January 6, 2021 as part of a “fun vacation” to see Washington D.C. and its monuments, and because she wanted to hear then-President Donald Trump speak. She was also interested in attending because Congress was certifying electoral college votes that day, and her “personal opinion is it was probably a rigged election.” Plaintiff testified that it was “crowded” but there was “no violence,” that she was friendly with “riot cops and military and stuff like that,” and that it “was really peaceful” like “just a normal rally.” She stated that she did not see or cross any barriers or barricades. And she testified that she believed it was lawful for her to be where she was that day. Indeed, she believed “that the rally organizers had a lawful permit.” When she returned home, Plaintiff stated her beliefs on a private Facebook page. To her surprise, Armstrong posted those comments and photos on her employer’s Facebook page. Two days later, her employer fired her. Plaintiff recalls that Robinson told her that she was fired for “inciting a riot.”

Of course, Defendant has a different characterization of the facts. Robinson denies that she told Plaintiff that she was fired for “inciting a riot.” And Defendant’s employees testified that Plaintiff was fired because she was present where she was not lawfully permitted to be on January 6, 2021. But deciding whether Plaintiff was fired for a political motive largely comes down to a credibility determination, and the Court does not make credibility determinations at summary judgment. A jury will have to decide which version of the facts is the truth….

Punitive damages may be awarded on a showing of “oppression, fraud, or malice.” … As described in the previous section, a reasonable jury could conclude that Defendant terminated Plaintiff with a political motive based on the nature of the events of January 6, 2021, the nature of Plaintiff’s experience that day, the nature of Plaintiff’s Facebook photos and comments, the differing recollections of the conversations surrounding Plaintiff’s employment termination, and other facts. For the same reasons, a reasonable jury could likewise decide that Defendant acted with malice in terminating Plaintiff’s employment.

Here’s what I wrote about the Complaint back in Jan. 2021:

[* * *]

Can California Employee Be Fired for Attending the Jan. 6 Protest at the Capitol?

Subtitle: California statutes suggest the answer may be no, so long as the firing is based on the political activity, and not on criminal conduct.

In Snyder v. Alight Solutions, LLC (filed yesterday), Leah Snyder claims that her employer fired her on these grounds. Here is what she alleges in the Complaint:

She listened to speeches being made and walked to the Capitol, and then she left. She did not participate in any rioting, she did not observe any rioting, and she did not hear of any injuries to persons or damages to property during her peaceful visit. On return home, she posted two “selfies” with her friends and at least one smiling police officer in front of the Capitol to a comment thread on the social media of Sean Armstrong. She believed she was engaging in a debate over the nature and scope of a protest at the Capitol….

On January 6, 2021, while on paid time off from work, she visited Washington, D.C. She and perhaps as many as one million other people, listened to speeches made by the President of the United States and other important persons. Plaintiff is not a zealous adherent of any system of beliefs. Her impression of the speeches was that the assembled people were being asked to peacefully show their support for the U.S. Constitution and the rule of law while presenting their displeasure with vote counting procedures during the recent national election. At the conclusion of the speeches, she joined a group of people who were peacefully walking to the Capitol. She reached the Capitol, took several “selfies” with friends, and at least one with a smiling police officer in the background. She did not cross or see any barricades. She did not see nor participate in any rioting. She did not enter the Capitol. She did not observe or hear of any injuries to persons or damages to property. She was not arrested and she did not see anyone who was arrested. On occasion, when she encountered police officers, she inquired if walking with the other members of the crowd was legal, and each time, the officers responded that what she was doing was legal. After spending some time at the Capitol, she left and went home.

She claims she was then fired because of those actions.

If her allegations are correct, then the employer likely violated California Labor Code §§ 1101-02. Those statutes (enacted in 1937) provide,

No employer shall make, adopt, or enforce any rule, regulation, or policy:

(a) Forbidding or preventing employees from engaging or participating in politics or from becoming candidates for public office.

(b) Controlling or directing, or tending to control or direct the political activities or affiliations of employees.

No employer shall coerce or influence or attempt to coerce or influence his employees through or by means of threat of discharge or loss of employment to adopt or follow or refrain from adopting or following any particular course or line of political action or political activity.

[1.] In Gay Law Students Ass’n v. Pac. Tel. & Tel. Co. (Cal. 1979):, the California Supreme Court made clear that “These statutes cannot be narrowly confined to partisan activity” (unlike some more narrowly written statutes in other cases, that are limited to activity related to parties or elections):

“The term ‘political activity’ connotes the espousal of a candidate or a cause, and some degree of action to promote the acceptance thereof by other persons.” The Supreme Court has recognized the political character of activities such as participation in litigation, the wearing of symbolic armbands, and the association with others for the advancement of beliefs and ideas.

Going to a political demonstration would thus be covered.

[2.] The statute seems to be limited to actions pursuant to a “rule, regulation, or policy”; and the California Supreme Court has defined “policy” as “[a] settled or definite course or method adopted and followed” by the employer. But, as the Louisiana Supreme Court held, interpreting a similar statute, “[T]he actual firing of one employee for political activity constitutes for the remaining employees both a policy and a threat of similar firings.” And such firing tends to coerce other employees: “[T]he actual firing of one employee for political activity constitutes for the remaining employees both a policy and a threat of similar firings” (I quote again the Louisiana case).

This is especially for large companies these days, in which employment decisions have become much more formalized and bureaucratized (in part because the process of hiring and firing has become a highly legally regulated activity). It seems unlikely to me that the employer (which apparently has 15,000 employees) will say, “Nope, this was just a one-off decision, we might well handle other employees completely differently”; generally, part of its argument would indeed be that there’s some policy that this 20-year employee has violated, which is why she was fired. This might be why some recent California cases have basically treated these sections as generally applicable to firings based on political activity, e.g.,

If plaintiff was fired for his particular political perspective, affiliation or cause of favoring Proposition 8 or being against same-sex marriage, so that it may be inferred that (as plaintiff alleged) Safeway was in effect declaring that the espousal or advocacy of such political views will not be tolerated—then Safeway’s action constituted a violation of Labor Code sections 1101 and 1102.

Ali asserts he was fired not because the content of his articles contravened the editorial policies or standards of the newspaper, but because outside of the workplace he publicly criticized an influential public official for supporting a particular political candidate. Whether Ali can ultimately prove all the elements of his claim, he has submitted sufficient evidence of a public policy violation to survive a motion for summary judgment

[3.] Now a California employer is free to fire employees because they committed crimes, or even because it believes they committed crimes, apart from their political activity. If, for instance, Alight the employer fires anyone who it has reason to think were engaged in a riot or vandalism, that isn’t itself firing for political activity.

But Snyder’s allegation is that she didn’t commit any crimes. And to the extent that the employer inferred that she must have committed crimes based simply on her attendance at the Capitol protest, I think that has to be treated as a restriction on political activity.

[4.] Naturally, all of this would equally apply to people attending any sort of protest, left-wing, right-wing, or otherwise: e.g., an anti-police-brutality protest at which some of the protesters engaged in vandalism or arson, an anti-abortion protest at which some of the protesters illegally blocked entrances to an abortion clinic, an anti-globalization protest at which some of the protesters violated the law, or anything else along those lines.

[ad_2]